Edited by: Maggie Rosenau

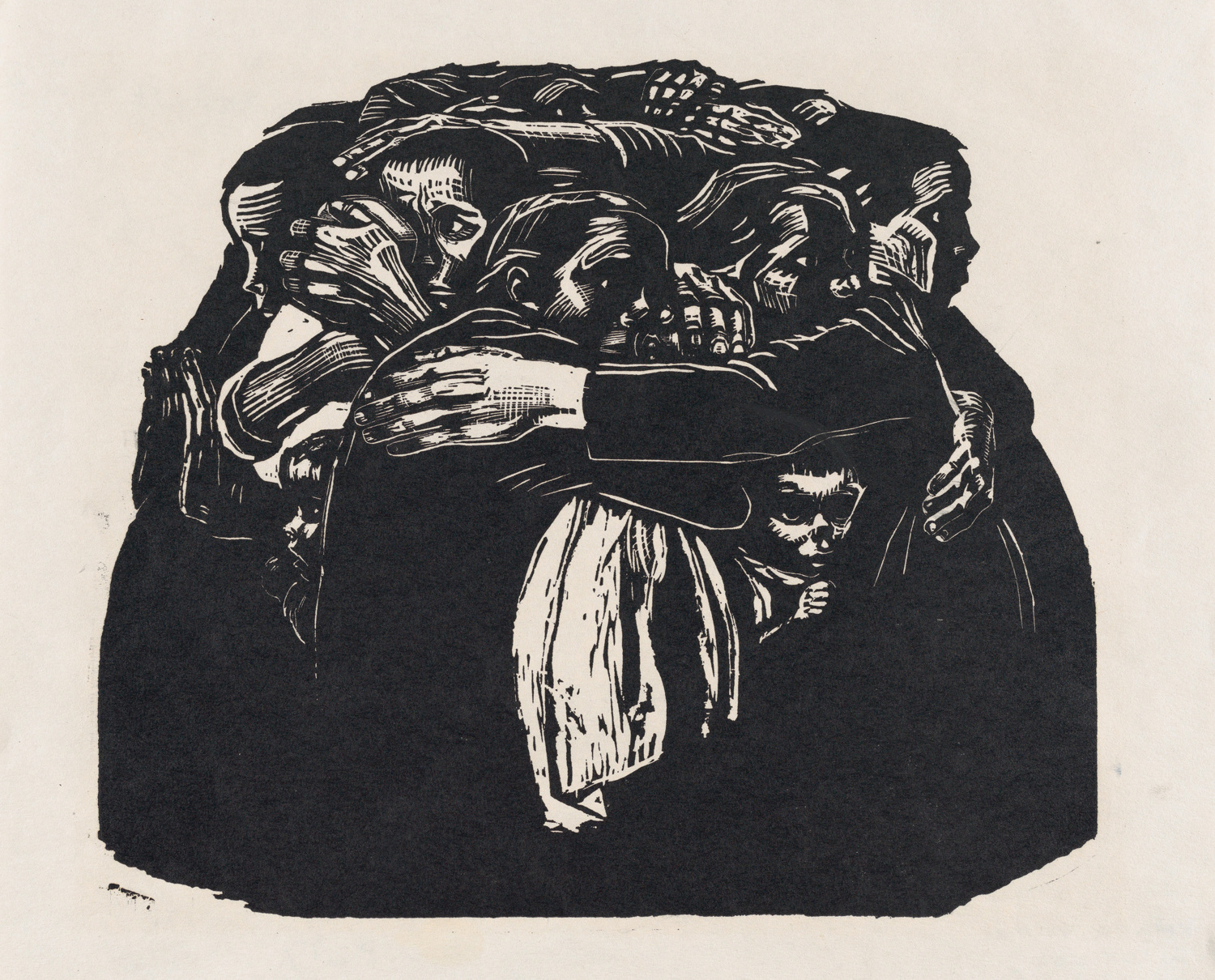

Artwork: Käthe Kollwitz

How would you kill another person along with you? With love? Let someone love you until they die if you die? But what if you did not die when your lover did die, and you just became a miracle – alive and feeling nothing?

These words were shared with me by an old man I met in Ward No. 12, a man whose only crime was having two sons who dared to rebel against the brutal regime and joined the the Free Army. So, of course, he and his two other sons were arrested and forced to pressure the two rebels sons. This man is called Abu Khaled.

I did not know his real name and it never occurred to me to ask, because men in my country are not asked their name by younger men. Instead, a man is called by his surname, which is also the name by which his first child goes. Abu Khaled had four sons and one married daughter living in Lebanon with her husband. He was home with his two sons when security forces arrested them and brought them here. After the first of three interrogations, they were separated from each other in the dormitories.By the time I got to know Abu Khaled in Ward No. 12, he had spent almost four months in the place. He was calm most of the time and the smile never left his face. He was so joyful when he began telling stories from the past. Sometimes he got angry when someone touched him or got in his personal space – something hard to avoid in a small place with a large number of people. We were in the same group together and often sat next to each other, so we shared our stories and the reason why we were here. We talked updated each other on the progress of our interrogations too. He told me about his sons, and I found out that he lived just five minutes away from my family home, so I started asking Abu Khaled about his sons. Perhaps I knew one of them from the neighborhood. He described them one by one and when he described his youngest son – a guy in my age named Muhammad – I realized he was indeed a friend of mine. Muhammad and I did not have a strong friendship, but I admired him as very brave. When the Revolution started, he was present at every single demonstration against the government. I always saw him cheering loudly against the Regime.

Abu Khaled was incredibly angry at Muhammad and his older brother. In the Ward, he cursed them and expressed remorse about not having raised them well. He couldn’t handle the idea that their actions against the government had put him here in prison with his two oldest sons. He also could not understand the “great cause” his sons believed and were participating in. My response to his rage about this was always “freedom.” I tried to explain that his sons were seeking freedom like most of us. But Abu Khaled never believed in this generation, our generation–the young people who went out to revolt against this government. He was always afraid of the regime, remembered well the civil war and “scorched earth policy” and what it all did to his generation—how in 1982 the government destroyed the entire city of Hama and killed a thousand people in one week. I eventually learned not to discuss these things with him because he didn’t want to understand his sons’ actions or have his mind changed. I understood his anger, though. Prison is no place for young and healthy people to care for and nurture elders, so I stopped pursuing this kind of conversation with him.

During the time I spent in this dormitory, I shared with Abu Khaled every detail of my investigation. He knew my whole story, including how I spoke with Hani and tricked him to reach my father and deliver him my letter. I told him about my concerns – what if Hani found out that I was lying to him?! What if he discovers that my father’s job is not actually what it seems, or if he reached my father and was refused payment? What if all of this leads to more trouble for my family? My worry began to eat away at me for the next three days, while I waited for Hani’s response. Abu Khaled was kind and shared all my concerns. He tried his best to keep me calm and relaxed, and we waited for the actions that would decide our lives.

- February 2013

It has been three days since I’ve spoken with Hani, now sitting in the same spot facing Abu Khaled in silence. At midday the dormitory was quiet. The cold was unusually heavy. They had told us early in the morning it was snowing and they would open the high windows for ventilation. It was no problem anyway – we loved to be cold more than burning in the heat of the dormitory. The light was nice and dim in the room because one of the two ceiling lights had been broken a couple of days ago. The cold soothed and brought everyone to their safe place inside them. Everything was calm until we heard the approaching sound of keys rattling in the corridor. That calm silence turned into a terrifying silence in our hearts. This was always the case whenever we heard that sound. Each person prayed that his ID number would not be called up for interrogation. The moment came though, and the key was inserted into the lock of our room. But before the door opened, the cell window opened and Hani’s face peeked in. He seemed be searching for someone. I raised my head up so he could see me my face in case it was me he was looking for. It was, and he gestured with his hand for me to approach him as he opened the door. I went out quickly, he closed the door behind me and walked me to the corner in hall. He looked at me and said: Your father refused to pay!

In that moment, however, I felt crushed. I don’t know what happened – I was already sure that my father would refuse to pay anyway, but why did I now feel a loss of hope? I searched Hani’s eyes to see if I was in trouble or if he had discovered my lie about my father’s work, but I detected nothing. I did not know how to respond to him. My psychological state began to reflect in my body and fear took place of stability in my voice:

Me: But, Sir… is it possible that he was not certain of your identity? I mean, did he read my letter?

Hani: Yes he has read your letter. At first he was not sure but then he seemed disinterested and asked me what is required for your release. We explained the payment, but he refused and said he doesn’t have this money. I gave him my number in case he changes his mind. So tell me, does he have this money?

Me: Sir, I am really not sure if he has this money or not, or even if he trusted you or the letter. Perhaps I can write another letter so he can be convinced?

Hani looked at me, thought for a moment, and then agreed. He told me to wait there while he fetched a paper and pen. While waiting there, facing the wall, many conflicting thoughts came into my head. I was stuck between my conviction that I had done what I had to do to let my parents know I was still alive, between knowing that my father would not be fooled into giving these people any amount of money, and between the little boy inside me who was holding on to the hope of getting out of this place in any possible way. I don’t know why I asked to prepare another letter. I was sure my father knew that I was the author of the first letter, so why was I doing this and putting more pressure on him? It is a thing I would come to regret in the following days. Hani returned with paper and pen, ordered me to quickly write a second letter and go back to my cell to wait for word about this second meeting with my father.

Later that day, I told Abu Khaled everything – how my father refused to pay and my suggestion to write to him again. Although my expectations were correct, I was sad and disappointed. I just really wanted to leave this place forever. Abu Khaled was kind of angry with my father’s decision, which made it harder for me to think about it all. I also became upset with my father. I don’t know why everything seemed to collapse in my mind. I expected all of this, but why was I suddenly so anxious about it all?

- February 2013…

My fear grew during those days following my second letter. Moreover, there was no sight of Hani for days.

But suddenly and without warning, the door to our cell opened this afternoon, and Hani stood there with another jailer named Ali, who loudly shouted: seventy-eight!

I quickly stood at the call of my number, went outside and was ordered to face the wall. I did. They locked the door and then ordered me to follow. I walked, followed their steps without raising my head, and when they started leading me up the stairs, I panicked.

I don’t know where it all went wrong. The second letter? My father? The lies I told Hani about my father’s job and the payment? Did he find out about it? These panicked questions stopped suddenly, though, when we arrived at the first floor and Hani turned to face me:

Hani: Your father refused to pay again. He made it clear that he has no money to get you out, but I don’t believe him. We want to help you, but your father seems a liar to me and does not seem to care about you. The investigator wants to ask you some questions, so don’t lie if you want us to help you!

Me: Yes, Sir!

They kept me waiting with my head against the wall for about five minutes. Then I heard the voice I despised most – the voice of my investigator.

Investigator: Seventy-eight! Come here!

As I walked toward his voice, my eyes covered, I was kicked hard in the stomach. The blow was so painful it brought me to my knees.

Investigator ( screaming ): Get up already, you damn animal! Stand up!

Me (standing): Yes Sir!

Investigator: Now tell me, you have a brother named Abdul who officially lives with your parents, correct? Where is he now?

Me ( shaking ): Sir, I have been detained here for more than two months, and the last time I saw my brother was over six months ago. The last I heard, he was in Beirut-Lebanon, so I really don’t know where he is or what is he doing now.

Investigator: You are a fucking liar!

The interrogation continued like this for about an hour or more and was filled with all the basic beatings, intimidation and torture – all this to try and find out where my brother was staying or hiding. And when I think about it now, the level of their stupidity is curious. What kind of information could they possibly expect to get by beating a detainee who had been there over two months?

I remained steadfast under duress and uttered no word that might indicate places my brother usually goes to. I guess I brought all this onto myself by writing the second letter. My father refused to pay again, which was unacceptable to them. They demanded the money now and it did not matter how they got it or with whom they could trade his prisoner son for cash. Well then, why not double it by detaining BOTH sons?

So that was their plan after all. They wanted a way to put more pressure on and get more money out of my father. How could he refuse if both his sons were imprisoned? But my brother did nothing against the government beyond participating in a few demonstrations. But those had nothing to do with why they were questioning me on his whereabouts. It was now clear to me.

The interrogation ended without desired results, and I was ordered back to the cell downstairs, where I sat again in my usual spot next to Abu Khaled. Fear clearly remained on my face. I told Abu Khaled what happened upstairs. He listened to my panicked explaining and tried to keep me calm, saying: “Your father has no idea what is happening here. If he learns about this place, he will pay directly, but right now he knows nothing about it.” Abu Khaled was really angry at my father, and so was I, but then again, this trouble was my fault so I couldn’t blame my father. My plan to deliver news that I was still alive worked. I don’t know how my hope turned into fear of consequences of my actions. And now my brother!

I looked at Abu Khaled as he tried to calm me and blurted:

Me: Abu Kahled, how long have you been here in this Ward?

Abu Khaled: This week marks six months for me and my two sons. And we are registered together in one case, so if I got my freedom they will also get theirs! If I will die here, my sons will die here too.

Me: Six months! That is so close to the term limit for elders! Abu Khaled, you know that for older people like you, six months is the limit if they are not charged with dangerous behavior, and you did nothing anyway. They must only want your sons, but six months is also enough time to know that your other sons will never turn themselves in! If by chance you are freed and get to see the sun again, could you go to my family and warn my brother to leave, perhaps even leave the city?

Abu Khaled: For sure. I swear that will be the first thing I do on my first day of freedom. I will tell them everything you have told me, and I might even convince your father to pay. Just pray for me!

Sometimes miracles happen in strange ways. We wait and hope, but it’s when you stop waiting and hoping things happen. And once those hopes are met, you wish you had hoped for more. That is how the human soul is – always seeking and wanting more.

The next morning Abu Khaled sat and quietly repeated his supplication to God:“When my heart hardened and my paths narrowed,

I made hope a stairway to your forgiveness,

My sins piled and overwhelmed me

But when I compared them to your forgiveness,

O Lord, your grace was far greater.”Over and over he repeated his supplication. I sat next to him with teary eyes, listening and thinking. Soon we heard the door key unlock the cell door. A new jailor appeared with a sheet of paper and called out numbers of three detainees. Abu Khaled then suddenly stood up and ran out of the cell. It was the freedom call. He looked back at me one last time as if to let me know he promised to visit my family and tell my story, so I rested.

During my remaining stay in that dormitory, I never knew if Abu Khaled had kept his promise, so what you will read next is from four months after Abu Khaled had received his freedom. We met accidentally in the neighborhood on a Friday afternoon, almost one week after I was released from prison. When I saw him I hugged him and asked how he was doing, so he invited me to his place to talk so no one could hear us. When we arrived, he made tea and started telling me all that had happened to him after his release:

Abu Khaled: When we left the prison, they took us to court. There I finally met up with my two sons who were arrested with me, and we were given a few hours together. That afternoon we went back home, I cleaned myself, put on some new clothes, and quickly made my way to your home to meet your parents and tell them to hide your younger brother. When I entered the street, I saw a twenty-year old boy walking toward me. I stopped him and I asked where I might find the home of Anas’s family. The boy responded, asking what exactly I wanted from them. I told him I wanted to speak with Anas’s brother and family. After a moment of quite thinking and scrutinizing, he said he was Anas’s brother and asked me what I wanted. I looked at him and asked: are you Abdulrahman? He gestured positively. I told him his brother sent me to instruct that you leave you home and the neighborhood and disappear for a while. They are searching for you and it will not be long before they capture you!

Abdulrahman looked at me, thanked me, and showed me the way to your parents. Then he disappeared as you wanted, and I sat with your father for long time. I told him everything about what I knew of you and your story. I made your parents aware of everything, and they seemed more comfortable knowing you were alive.

Me: And what about your rebel sons? Where are they now?

Abu Khaled looked at the ground and started crying.

Abu Khaled: I don’t know where to begin. I don’t know how or when I made my mistake. I don’t know if I was a good father to them, but I am now certain that I messed up. They were fighting with the rebel army when Muhammad was shot in the chest and died instantly. His brother carried his body away and wanted to bring it home, but while he was driving the car, a shell fell from the sky, hit the car, and he also died that day next to his brother. All of this is my mistake – I did this to them. You see, I was angry and prayed to God they be punished for what they caused me and their other brothers. Every day I prayed with anger, and God listened to my supplication. How could a father wish bad things on his sons!? What kind of a father am I? And what life remains for me – to live with what I did? They left me and left this world and broke my heart and their mother’s heart. How could they have done this? How would you kill another person along with you? With love? Let someone love you until they die if you die? But what if you did not die when your lover did die, and you just became a miracle – alive and feeling nothing? And here I am still alive, feeling nothing anymore. I have no need for anything more from this life. I wait patiently now for my death. My two sons have left the country with their mother, and here I am, alone, between these silent walls still wondering where it all went wrong. I don’t know anymore. May God rest their souls in peace.

We cry for those who have gone, mourn those who have departed, weep for those who perished while in poverty. But we also cry for ourselves. For we are afraid to be afraid, approaching our end, losing our existence and eventually becoming nameless.

O all this world, here we are.